... über Peter Vogel

- Joachim Schneider über Peter Vogel - deutsch

- Nicoletta Torcelli, Translation Peter T. Hill - english

- Francine Flandrin - francais

Joachim Schneider über Peter Vogel

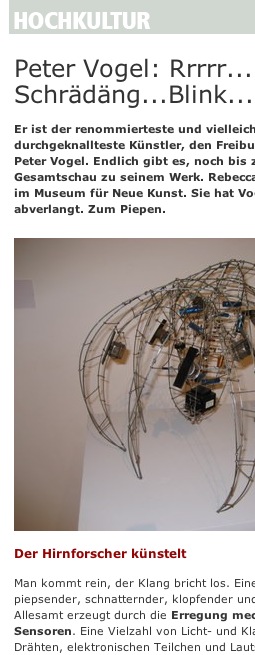

Eines können die Objekte von Peter Vogel nicht verleugnen. Bei aller schlichten Schönheit, bei allem ästhetischen Reiz, der von ihnen selbst in ihrem Ruhezustand ausgeht - sie wecken Erwartungen. Schaltkreise, Lautsprecher, Lämpchen, Flügel - bewegliche, leuchtende oder klingende Teile sprechen eine unmissverständliche Sprache: «Hier ist Bewegung, hier gibt es Licht und Töne. Schalt mich an!»

Doch selten gibt es den Knopf, den Schalter zum Umlegen. Peter Vogels Objekte sind in der Regel mit Sensoren ausgestattet, sie reagieren auf Schall und Licht. Sie verlangen, dass der Betrachter näherkommt und sich ihnen widmet. Sie brauchen ein Gegenüber. Erst mit ihrer Initiierung entwickeln die Objekte eine Eigendynamik, als wären sie lebendig. Sie sind nicht nur Skulpturen, sondern auch Klangkörper und/oder Maschinen, sie sind kaum zu kategorisieren, zumal sie erst in der Interaktion ihren Sinn und Zweck erfüllen.

Peter Vogel ist ein Pionier der interaktiven Kunst. Das spielerische Moment seiner Werke wurde schon vielfach thematisiert: Nicht nur dass der Betrachter beim Kennenlernen der Objekte unterschiedliche Sinne aktivieren muss, der spielerische Umgang mit den Skulpturen und Wandobjekten fordert gleichzeitig den Intellekt: Deren Bewegungen respektive deren aufklingender Output werden von einem komplexen System hervorgebracht. Der spielende Betrachter kann sich vertiefen in unterschiedliche Zusammenhänge auf unterschiedlichen kategorialen Ebenen: Struktur und Effekt, Ursache und Wirkung, Zeit und Raum, Chaos und Regel, Notwendigkeit und Zufall. So illustriert beipielsweise das Objekt «Blaue Lichtpunkte» (2003) etwas, was Peter Vogel einen «determinierten Zufall» nennt: Streng determinierte Reihen erzeugen im Zusammenspiel ein Chaos, das dem Betrachter Rätsel aufgibt. Von Peter Vogel selber existiert eine handschriftliche, philosophische Begriffsbestimmung des Spielens. Sie endet mit Schiller: «Der Mensch spielt nur, wo er in voller Bedeutung des Wortes Mensch ist, und er ist nur da ganz Mensch, wo er spielt».

Mag es auf den ersten Blick kurios erscheinen, dass Schiller in Zusammenhang mit Dioden, Schaltkreisen und Photozellen zitiert wird, dass ein humanistischer Leitsatz zu komplizierter, womöglich sogar entfremdeter Technik herbeibemüht wird, noch rätselhafter aber scheint die Frage, wie ein Bildender Künstler Schillers Diktum in Plastizität sprich Faktizität verwandeln kann. - Die Anwort steckt schon in dem kleinen Wörtchen Wo, es geht um die Spiel-Stätte.

In der Bildenden Kunst kann dies nur bedeuten, dass der Künstler einen Raum kreieren muss, der das Spielerische schon in sich birgt. Einen Raum, in dem der Betrachter seine passive Rolle aufgibt und aktiver Teil des Kunstwerkes/ Objektes wird. Erst dann entsteht auch Interaktivität: Wenn komplexe Reaktionsschemata der Objekte geradezu zum Spielen auffordern. Dabei sind es bei Peter Vogels Modellen nicht nur die Lichteffekte, Geräusche und Töne, die einen virtuellen Spiel-Raum schaffen, sondern schon im Moment der Begegnung, der Initiierung des Objektes entfaltet sich ein Spiel-Raum in der Zeit.

Peter Vogels künstlerischer Werdegang kann man verstehen als ein Erschliessen und Erforschen von neuen Räumen für die Kunst, Objekträume respektive Spielräume neu abzustecken und zu definieren. Er begann als Maler, studierte Physik. Nach zehn Jahren Berufstätigkeit in der Forschung widmete er sich ausschliesslich der Kunst. Seine Bilder sprengten den zweidimensionalen Rahmen, indem Teile der Bild-Komposition auf den Betrachter reagierten: Ein Gummischlauch schnellt nach oben, eine Lampe leuchtet. Im Bild «Drehstäbe» aus dem Jahre 1970 bewegen sich schwarze Stäbchen auf weissem Grund, indem sie Schatten rezipieren. Seine ersten kybernetischen Objekte waren eine Art lebendige Einzeller aus Drahtgeflecht, die sich von Licht ernährten.

Zwar waren die drei Aspekte Sichtbares und dessen Entgrenzung, sowie das interaktive Moment (Verhalten und Reaktion) schon in den ersten Objekten erhalten, aber ihre Funktion, ihr Eigenleben blieb im Verborgenen, versteckte sich hinter Leinwand, Plastik und Farbe.

Ab 1971 verschwand die Malerei ganz aus Peter Vogels Schaffen, 1975 verzichtete Peter Vogel darauf, elektronische Bauteile und die Drähte schwarz zu lackieren: Nur noch das nackte, ursprüngliche Material soll zu sehen sein und eine Ästhetisierung der Objekte nicht von ihrer eigentlichen Bestimmung ablenken. Die technischen Bausteine und der Draht entsprechen Farbe und Pinsel, deren Anordnung und Auswahl wird allerdings diktiert von der Funktion wenn man so will vom Innenleben des Objektes: «Form follows function».

Offen, durchsichtig und minimalistisch - gewissermaßen «aufrichtig» begegnen Peter Vogels Skulpturen und Wandobjekte dem Betrachter. Das macht seine Arbeiten so einzigartig: Sie wollen nicht beeindrucken (obwohl sie das tun), überwältigen, manipulieren, Furcht einflössen, Gefangennehmen, eine (selbstreferentielle) Gegenwelt entwerfen, obwohl in ihnen ein Stück Utopie steckt.

Sie sind da, um zu kommunizieren. Es sind offene Systeme, in denen der Mensch eine wichtige Rolle spielt. Noch dazu schimmert durch ihre Transparenz ein Licht auf unsere medial vermittelte Welt. Zwar steckt auch in Vogels Objekten (zumindest für den Nicht-Techniker) ein Geheimnis, doch es tritt offen zutage. Während in anderen medial vermittelten Kommunikationsräumen wie dem Cyberspace der Raum zum Mythos geworden ist, darin aber die Körperlichkeit des Menschen auf der Strecke bleibt, konfrontieren Peter Vogels interaktive Objekte ihr Gegenüber stets mit dem elektronisch geschaffenen Raum, in dem sich der Mensch mit seinem Körper so oder so verhalten kann. Gibt es tatsächlich so etwas wie einen virtuellen Raum, dann sieht er so aus.

Mit diesem dekonstruktivistischen Moment machen Peter Vogels Objekte auch im Computerzeitalter noch Sinn.

«In unserer hochtechnisierten Welt werden archaische und zutiefst menschliche Bedürfnisse mit immer komplizierteren Apparaten befriedigt.» Sagt Peter Vogel. Wie das funktioniert und gleichzeitig inszeniert wird, zeigen seine Objekte. Mit verhältnismässig einfachen Mitteln. Anachronistisch sind sie deshalb noch lange nicht, die blinkenden, schnarrenden oder tönenden Skulpturen.

Nach dem Bezug auf Paul Klee, dessen «Zwitschermaschine» Peter Vogel in den 80er Jahren in einer Serie von Objekten kongenial vergegenständlichte, erfährt nun der belgische Künstler Panamarenko eine Hommage. Dessen ausgeklügelten, fantastischen Flugzeugen, die sich der Beschleunigung und damit der Ökonomisierung verweigern, widmete Peter Vogel eine Reihe kleiner «Flugobjekte, die nicht fliegen».

Die Hommage kommt nicht von ungefähr. Gemeinsam ist den Objekten die Verweigerung der Simulation. Sie sind nicht mehr als sie sind, nur das, was sie darstellen. Doch verglichen mit Panamarenkos monströsen Gebilden fehlt bei Vogels Miniaturen das Telos: Das (Nicht-) Fliegen kehrt zurück ins Reich der Metaphysik, allein die Bewegung zählt: Das «Flattern», das «Auf-der-Stelle-Schwimmen». «Meine Figuren sind ironische Allegorien auf Beziehungsstrukturen, seien sie nun zwischen Menschen oder zwischen Mensch und Maschine, Technik und Gesellschaft.» Hat Peter Vogel einmal gesagt. Zwischen Mensch, Kunst und Medien kann man noch hinzufügen.

Joachim Schneider"Time - sounds"

Nicoletta Torcelli, Translation Peter T. Hill - english

For a time Peter Vogel (born 1937 in Freiburg) bestrode the two worlds of art and science. From 1957 to 1975, while first studying then doing research as a physicist, he was also involved in the visual arts, dance and choreography, as well as composing electronic music. As an artist his original leaning was towards informal painting. The initial impetus which was to bring about a radical change in his formal language was provided by a scientific experiment conducted by the English neurophysiologist Grey Walter in cooperation with various psychologists, which came to Vogel's attention in 1967. He was greatly fascinated by the "machinae speculatrix» devised by Walter - rudimentary open systems capable, through the media of light, sound and sensors, of reacting to impulses from the outside world. In 1969 Peter Vogel made his first cybernetic objects. Since then, sensors, resistors and transistors have been part of his craftsman's toolkit. It is no coincidence that his contributions to international group exhibitions have been classified as "Science&Art» or "Art & Technology»: Vogel works almost exclusively with industrially produced components. The natural effect created by the objects is a highly original blend of industrial functionality and a filigree aesthetic, itself standing as an archaic metaphor for the industrial world.

An exhibition in Freiburg in 1971 was followed by numerous shows. To name only some of the more recent: he showed work in "Les Machines Sentimentales" at the Centre Pompidou in Paris (1986); in 1990 he took part in the "Image du futur" exhibition in Canada; in 1991 he showed work at the "Multimediale" festival at the Centre for Art and Media Technology in Karlsruhe, Germany; in the same year he was represented at "Artec" in Nagoya, his third appearance in Japan. Most recently, his 1992 work was shown at the exhibition "Chance as a Principle" at the Wilhelm Hack Museum in Ludwigshafen, Germany. Works completed as part of the "Art in Construction" series include the "Sound Triptych" in Villigen in 1991 and the light and mirror towerin Trier (1992).

There is an underlying continuity in the evolution of Peter Vogel's formal aesthetic language: since developing the basic concept for his "cybernetic objects", a central theme has run through his work like a continuous thread: it is the aspect of communication, the interactive processes between sender and receiver; the media of communication he employs are light, shadow and sound. In his current work his attention has focused increasingly on the integration of the principle of chance. These works are the product neither of chance nor deterministic forces: they are influenced by both elements, in a constant state of interaction which cannot necessarily be considered separately since the borderlines are not clearly defined. In dealing with the principle of chance and integrating it as a creative element, Peter Vogel is in fact taking up a tradition which is an essential strand in the art of the 20th century. The processes of randomness, developed in such techniques as "thrown" compositions, frottage, automatic writing, through to smoke pictures and action painting, have one thing in common: the traces of a structure, which cannot be planned in advance, but arises as a unique occurrence out of the process of painting, are thematized in explicit fashion. For example, in "Fluxus and Performance" the process of aestheticization is even more strongly radicalized: the work of art becomes a one-off gesture - not a product but an event, not an enduring singularity, but something transient and finite. No one who listens to time would maintain that time passes silently: it is as noisy as life itself - it is not time that passes, but being.

For Peter Vogel too, the aesthetic process, in which art interweaves itself with time, plays a central role: "Rendering time audible" was always one of his concerns. For the decade following 1969 he saw his objects primarily as "behavioural structures" - not as mimicry of nature, but imaginary systems: a metaphor for neuronal structures. At that time the deterministic nature of the objects was not questioned: the circuits were designed deterministically like neuronal networks; i. e. their behaviour, divorced from the environment, was assumed to be predictable. An object made in 1971 was an exception: in "Aleatory Triplet", an initial external impulse sets the three wings in rotation, which automatically stimulates the photocells, controlling by means of this feedback process their own rotation. This closed interactive system results in chaotic behaviour. In the other works, "chance" was not consciously thematized, but was constantly integrated in the sense of spontaneity: the reactions of the objects can be described as unpredictable and therefore random, because they are the result of explorative strategies, of the most diverse possible actions of the recipients approximating, in the purest sense of the word, to the work. The character of the works can be summed up in a single word: interactive. They are an invitation to play. Eye, ear and body are involved in equal measure. The human recipient becomes at the same time an actor. In this force field of sensual perception and physical reaction it becomes clear that art is "happening", being created and passing away again. This gives us a further general characterization for Peter Vogel's works: they are "time objects". Basically, they are simultaneously material and immaterial. They exist in two states: if they receive no external stimuli, they persist, visibly as aesthetic objects, in their static state. However, the essential aesthetic structure is a dynamic one that is connected with the irreversible process of time. In the execution, a topical and unique form is created, which is essentially unpredictable and unrepeatable. It is the result of a constant interaction between the preprogrammed mechanism and its actualization. But at the time, the fact that this interaction of objects with the environment sometimes generates chaotic structures in the system itself, structures which are no longer predictable, was a paradoxical phenomenon not apprehended by the artist.

The sound walls which Peter Vogel began creating in 1984 represent a synthesis of those long years of preoccupation with cybernetic systems which integrate musical experience. In these "materialized scores", as he calls them, he uses the principles of composition employed in minimal music: the primary goal is to generate the necessary sensitization for the secondary melodies arising out of the phase shift of repetitive musical structures, particularly for the differentiation of rhythms created in the overlapping fields. At the end of the eighties, however, there were signs of a clear shift of interest in the artistic concept. Peter Vogel described it thus: ''The discovery that, by overlaying consistently similar elements, one could create different, non-repetitive structures was fascinating and just as paradoxical as the creation of chaos out of deterministic structures, a realization that kindled my interest in chance. I discovered that the interaction between the observer and the object can generate quite different types of randomness." This preoccupation with the function of chance as a constitutive element in a work of art was the starting point for a series of works under the heading "Chance and Necessity", a theme Peter Vogel is exploring in all its diverse manifestations to this day.

In "Aleatory Quartet", created in 1990, Peter Vogel explicitly thematizes aspects of randomness in the interaction with the recipients. The sound object constantly changes its inner state; each new shadow stimulus creates a new sound constellation which is defined by the complexity of the system. Because the momentary state of the system is unrecognizable to an external observer, the subsequent reaction is unpredictable: one and the same movement/stimulus can have quite different consequences. Chance is related here to the impossibility of completely comprehending a complex system from "the outside" and "getting to grips with it" through the predictability of its behaviour. In his installation, with its architectural connotations, the five-metre high tower in Trier that was completed in 1992, both "determinism" and "chance" are consciously thematized, the former through sound sensors which transform all noises into light-borne information, a level which is deterministically structured, i. e. the behaviour of light diodes remains predictable. While chance comes into play in the integrated rotatable mirrors, fitted with light sensors, whose movements are activated only by direct exposure to sunlight. It is by means of these mirror rotations that the architectural elements are integrated into the work of art, because the splitting of the light beams reflects in flashes onto the surrounding walls, creating vibrating movement. The shifting surfaces of the mirrors and thus the reflections cannot be predicted with any certainty: air temperature and humidity, slight frictional losses through the moving parts, vibrations in the surrounding space - myriad unknown factors influence the sensitive rotary mechanism.

In the series of "Shadow Orchestra I - III" created since 1989, the focal point is instruments which play themselves and are projected onto the facing wall as silhouettes. The instruments, fitted with strings, bells, drums and cymbals, are set in motion through the effect of shadow play on the sensors. Sounds are created by plucking, stroking and beating. Thus, all the instruments can be used individually and autonomously, though also in relation to the others since all are bound by the same underling rhythm. The sounds thereby generate their own dynamics' in the complex system of subtle interactions, of minute irregularities. They are reinforced, subject to interference, diverted and repulsed, in the same way that we too are caught in a complex web of interactions in all our activities.

Peter Vogel - Link No.13

Shin Nakagawa - Interwiev 1992

Francine Flandrin - francais

Influencé par Grey Walter -neurophysiologiste et concepteur de structures électroniques à partir de schémas comportementaux-, Vogel envisage le spectateur comme performeur et non comme simple observateur. Physicien de formation, ses recherches réifient la pensée constructiviste selon laquelle : "nous n'avons pas besoin d'un mausolée de l'art où adorer des œuvres mortes, mais d'usines vivantes de l'esprit". S'appropriant la phrase de Friedrich von Schiller "l'homme ne joue que là où, dans la pleine acceptation du mot, il est homme, et il n'est tout à fait homme que là où il joue", l'artiste conçoit d'insolites sculptures et environnements sonores, mobiles et lumineux qui interagissent aux stimuli extérieurs -ombres, déplacements, bruits- et déclare trempé de neuroscience: "je n'ai pas pensé à la forme lors de la construction de ces objets, mais bien à leur comportement. On pourrait leur appliquer l'ancien credo du Bauhaus, form follows function" puisque à son sens, ces ensembles composés de systèmes unicellulaires ne deviennent art que, lorsqu'ils sont expérimentés.

C'est ainsi qu'aimanté par l'attraction de ces intrigants modules filaires aux diodes clignotantes et aux hélices tournoyantes, le visiteur se transforme en performeur, et expérimente à grands renforts de moulinets et vocalises les réactions de ces systèmes autonomes, tout en guettant les conséquences de ses actes, ou en essayant de reproduire certains sons -ce qui soit dit en passant est inutile, puisque l'action d'un observateur/performeur n'induit pas toujours la même réponse de l'objet sonore-. Pourquoi? Parce que la performance s'appuie sur l'immédiateté, contrairement à l'interprétation qui s'appuie sur la répétition.

Soumis à leur environnement, ces circuits réagissent à partir de la logique aristotélicienne: conjonction, disjonction, négation, auxquels Peter Vogel ajoute intégration et pré intégration. Imaginons une sculpture équipée de capteurs sonores; programmée pour devenir lumineuse sous l'effet du son, elle illustrera la logique de la conjonction, une autre équipée de cellules photo-électriques restera silencieuse si elle est privée d'ombre, ce sera la logique de la négation, bref pour Vogel comme pour Cage, ce n'est pas le compositeur, mais l'auditeur qui fait la musique. Partageant avec La Monte Young, une fascination pour l'indétermination dans la composition et l'interprétation, Peter Vogel livre l'action à l'autre afin qu'il enrichisse sa perception sensible, mais par le jeu, surtout par le jeu! Indexant aux principes d'échanges son travail, il propose une pensée politique, qui proche de Cornelius Cardew soustrait la musique aux systèmes de notation préétablis, afin de nous permettre d'élargir le champ de nos expériences.

Peter Vogel -

interaktive Objekte

interaktive Objekte